The Forgotten

Minatu Ijatat had had enough. The 62 year old Sahrawi refugee had arrived in the dusty Ausserd refugee camp in the desert of south west Algeria with her family in 1976 after fleeing their home in Western Sahara when Morocco, claiming the Western Sahara territory as theirs, invaded and war broke out. More than 4 decades later she was still in the desolate camp and losing hope of ever returning home . A referendum giving Sahrawis , the indigenous peoples of Western Sahara, the opportunity to choose between independence and integration into Morocco which had been the basis of a 1991 UN supervised ceasefire agreement , had , thirty years later, still not been held. Nothing was happening . It was the last straw.

Minatu Ijatat, 62, in front of her tent at Sahrawi Ausserd Refugee Camp in Algeria, May 2024

Minatu packed a few belongings and, feeling hopeful for the first time in years, joined a group of about 200 from the Ausserd Sahrawi refugee camp in Algeria and set off in a long parade of beaten up vehicles headed to Guerguerat, a buffer zone on the Mauritanian border, to make their own peaceful protest.

Roughly 150 of the group weathering the harsh, 3 day journey over 2000 ks of desert in scorching heat, were older women, women who remembered life in their Western Sahara homeland before being forced to flee. ‘We all forgot that we were this age. We were full of hope - full of strength. Despite our age, despite the struggle, despite being sick, we forgot all that. We just wanted to go there to defend our legitimate right to exist in our western Sahara, ' Minatu says, as she pours tea on a recent night, sitting in the sand in front of her home in the Ausserd camp. ‘We were full of hope that this could do something. Our protest there and just being there, we were hoping that that would just do something.'

The group built jaimas - the Sahrawi traditional tents and settled there. During the day , they would stand in a line in front of the border, closing the crossing. They were confident their peaceful tactics would work. ‘We didn't want a car to pass there. And that's because we thought it would force a solution from MINURSA [[ the UN peacekeeping force ]] , and force the other people who are the decision makers, to hear us, to know that we're closing this until you give us our rights.’

The Sahrawi flag is illuminated by the setting sun as it hangs from a 'jaima', the traditional Sahrawi tent, at the Fisahara festival held annually in the Ausserd Refugee camp . May 2024

It didn’t work. 20 days after they had arrived, Morocco used force to remove the protesters. The protesters didn’t hang about.

‘We left straight away,’ Minatu says, ‘The moment they started shooting at us , we came back here.’

Brahim Ghali, pictured below center, President of the Sahrawi Democratic Republic, citing Morocco’s incursion into the ‘buffer zone’ where the protesters had been , declared the ceasefire over. It was the 14th November 2020.

Brahim Ghali, center, President of the Sahrawi Democratic Republic being greeted warmly by Sahrawi refugees at the Ausserd Refugee Camp at the annual Fisahara Festival . May 2024

War between Morocco and the Sahrawi resistance army known as the Polisario Front, largely dormant since the 1991 ceasefire, resumed in earnest. Thousands fled their homes in the ensuing bombardment in the ’liberated territories’— as Sahrawis call the 20% of Western Sahara not occupied by Morocco . More than 4000 flooded into the Ausserd camp alone.

Sidate side Bahia , 80 and Naim Ahmed Salm lmbarki , 76 were amongst them.

Sidate Side Bahia , 80, left and Naim Ahmed Salm lmbarki , 76, lying down, in their new home in the Ausserd Refugee Camp 2024

Today they are in their home at the Ausserd Refugee Camp. It has been 4 years since they arrived here, but their suitcases remain piled up neatly against the bare concrete walls, as if waiting for an imminent return to their real homes.

Both men are war veterans. Both had fought long and hard with the Polisario Front against Morocco’s occupation in the 16 year Western Sahara War, conducted betweenthe years 1975-1991. Then, armed with just kalashnikovs and cars, they had managed to counter Morocco’s f-16’s and Mirage fighter jets and wrest control of territory. But now, Morocco is using drones and they have no way of taking them on.

When they heard the ominous sound of the drone motors nearing their homes, they had no choice but to flee for their lives.

‘ The drones were there 24/7, ‘ Naim says sadly. ‘ We had no time — we left only with a car. We left everything else behind - all our animals, everything.'

Dogged by the trauma of leaving their homes and animals, haunted by memories of the drones, the bleak and isolated camp offers little consolation.

'The USA said they would find a solution for us but for 30 yrs, we are still waiting for a solution, ‘ Naim says, ‘We show ourselves to the world and the world says we are bad people - how can they think its bad to want our own land ??’

’ Since coming here , I have been sick . I have felt my power slowing step by step.'

Sidate, next to him, hangs his head .

A Mirage fighter Jet, downed in the 16 year war between 1975-1991, on display at the National Museum of Resistance . Back then, fighters brought down sophisticated aircraft with nothing more than their Kalashnikovs.

Sidate Side Bahia

As Naim and Sidate, along with thousands of others, streamed into the camps with the resumption of war, thousands , frustrated by decades of inaction waiting for a referendum , left to join the fight - so many, in fact, that volunteers were turned away, to await a later stage. Despite being forced to flee his home , Naim is pleased war has reignited. 'To me it’s a gorgeous thing starting the way [ to regain our land] , ' he says , 'War is a bad solution but it’s a beautiful situation compared to living like this here.' It is a widely expressed sentiment.

Muhammed Judu , 32 , Mohamed Lbachir 34 yrs old, and Buda Mohammed Buda, 33 , are combattants. The three lifelong friends, born and raised at the nearby Layoune Refugee camp, left to join the Sahrawi People's Liberation Army as soon as the ceasefire ended. They are on a 12 day leave when we speak at the Ausserd Refugee camp, where they are helping with security at the Fisahara festival .

Mohamed Lbashir, pictured left, explains why so many rushed to join the fight.

'As Sahrawis, we never ever believed in violence and we waited and waited for the international community to do something . When the ceasefire happened, they said they would do a referendum for us to go back to our homeland but no one did anything. '

'We had to do something . We never chose violence . We never wanted war .

But how else would get our Western Sahara ? '

Mohamed Lbachir top, at the Fisahara Festival, below , at the front (photo courtesy of Muhammed Budu)

Mohamed Judu , left, and Buda Mohammed Buda, right, at the front ( photo courtesy of Mr. Lbachir and Mr. Buda)

At the front (courtesy of the fighters)

' We believe that it is a chance and opportunity, ' Lbashir adds, ' Somehow we believe it is the only chance , the only opportunity to free our people.'

It is also an obligation.

'Every single man here goes to fight, even musicians . Even ten yr old children want to go to the war.'

'If you didn't go, your parents would be ashamed. They would tell you 'We don't want you here. We want you to go.' Nonetheless, it is not an easy decision, Lbashir admits. 'We are leaving our family. We are leaving our children. We're leaving our wives. We're leaving our parents, our sisters, our brothers, our beloved people here to go to fight. This is not easy. We are leaving our beloved ones.'

They don't know if they will come back.

Official numbers of the dead and wounded are not available but in Lbashir's 200 person battalion , 11 have been killed and 15 injured in fighting he describes as 'neither easy nor severe' in recent months.

'What is hardest, is when a friend dies there and you are sad, ' Lbashir adds, 'But at the same time you're happy - sad as he left his family but happy for him to be a martyr.'

Death has haunted every family over the long years Sahrawis have been fighting to reclaim their land. Five of Lbashir's uncles have been killed in combat, while his father too died eventually from wounds incurred fighting in 1975.

Reclaiming their Western Sahara homeland, whatever that might involve, whatever consequences it might incur, is seen as nothing less than an existential mission.

'What we believe in, is that one is to fight for our own legitimate rights to our Western Sahara - or , ' he says, determination in his eyes, 'Die.'

The lethal hazards of the advanced Moroccan military drones - supplied to Morocco by Turkey, China and Israel - which have transformed the battlefield, do not solely affect fighters. Civilians and animals are also being targeted. According to a recent investigation by the French newspaper L'Humanite , Morocco - using Israeli drones - have killed 86 civilians , two of whom were children, and injured another 170 since 2021 .

A chart on the wall of the Sahrawi Mine Action Coordination Office (SMACO) office in Buj Dor, Algeria , puts faces to some of the civilians killed in drone strikes

The approximately 174,000 Sahrawis in the five Sahrawi refugee camps in the Algerian desert live on hope. Shorn of their homeland, their animals and traditional nomadic lifestyle, their firm conviction that they will be able to return to Western Sahara one day is the glue holding the community together in camps which offer shelter, and little else.

Ausserd Refugee camp, May 2024

Refugees play games in the camp sand, improvising pieces and a board at the Ausserd Refugee camp, May 2024

It seems an increasingly difficult goal as the international community , motivated by investment and their own foreign policy agendas, line up on Morocco's side. France and Spain have both acknowledged their support for Morocco's proposed Western Sahara 'autonomy' plan, a plan , rejected out of hand by the Polisario, which gives nominal self governance to the Sahrawis, while British parliamentarians and the influential British think tank Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) are advising the UK government to do the same.

France has recently committed to funding a 3 megawatt power cable running from Dahkla in the Western Sahara to Casablanca, more than 1600 kilometers to the north, while Morocco is building additional facilities to export Western Sahara's valuable potash, attracting even more investors.

The most damning blow, however , was in 2020, when, under the auspices of Trump's Abraham Accords , the USA agreed to recognise Morocco's sovereignty over Western Sahara in exchange for Morocco recognising Israel .

It has left the Sahrawis in an even more precarious position with few supporters.

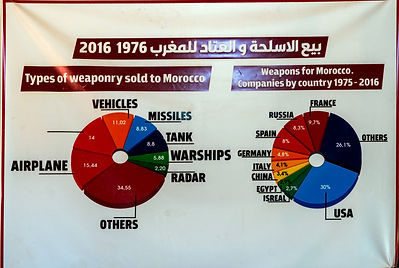

A chart hangs on the wall in the offices of The Sahrawi Mine Action Coordination Office (SMACO) in Bouj Dor, Algeria, details the countries who supplied Morocco with weapons, thru 2016

' I just see people dying and no one seems to notice,' implores Mant Ajulha, 19, sat on the floor in the unfurnished salon in her home in Ausserd Refugee Camp.

'The world has forgotten about us.'

Mant is tearful as she talks about Western Sahara, a place she has never visited but which defines her life. Born in Ausserd Refugee camp, she sees her life corralled by the plight of the Sahrawis. She will not achieve her goal of being a doctor nor will she have children, she says, only to subject them to the punishing limitations and conditions of life here.

' We want to leave here . We want to return back to our land . It’s our real land,' she says, her eyes brimming with tears,

' Why do we have to live in another land with another people? Why do we need someone else to help us eat and help me go school ?

We don’t - we wouldn’t need any of that in our own country.'

IMant Ajuhla, 19, in her home at the Ausserd Refugee Camp

'It’s so difficult to be born in a refugee camp and hear people talking about your land, and saying, "Oh, it has a beautiful beach, it has beautiful fish,' she sighs.

Yet, even in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds , the Sahrawi's belief that they will reclaim and return to their land endures.

'We have lost a lot, here and in the occupied territories . We have seen a lot of death - we have lost many people. But the one thing that we are aiming for, the one goal that we want - and we know we have the legitimate right to - is going back to our homeland in Western Sahara . And I do believe that we will go back there one day, ' Minatu says, as the night closes in.

' I am never disappointed by what I have been through and what the Sahwari people had been through, because I believe that this is a long term battle to free Western Sahara. I will never be disappointed. I believe that we will have our free Western Sahara, if not my generation, then maybe the next generation, or maybe the generation after that. But we will never stop , that's the fact. We will never stop, none of us as Sahrawis will ever stop until we get our free Western Sahara. '